Halloween and Kuchipudi

05 Nov 2017

Reading time ~16 minutes

A bunch of stuff went down this week not limited to what I’ll be sharing with y’all in this post. The other stuff mainly entailed casual meetings and discussions with key stakeholders in my project who I look forward to formally interviewing at later dates or being connected to other people with whom I may meet and interview in the near future. The reason for this lack of comprehensiveness is a lack of time in producing these blogs. Nevertheless the struggle continues…

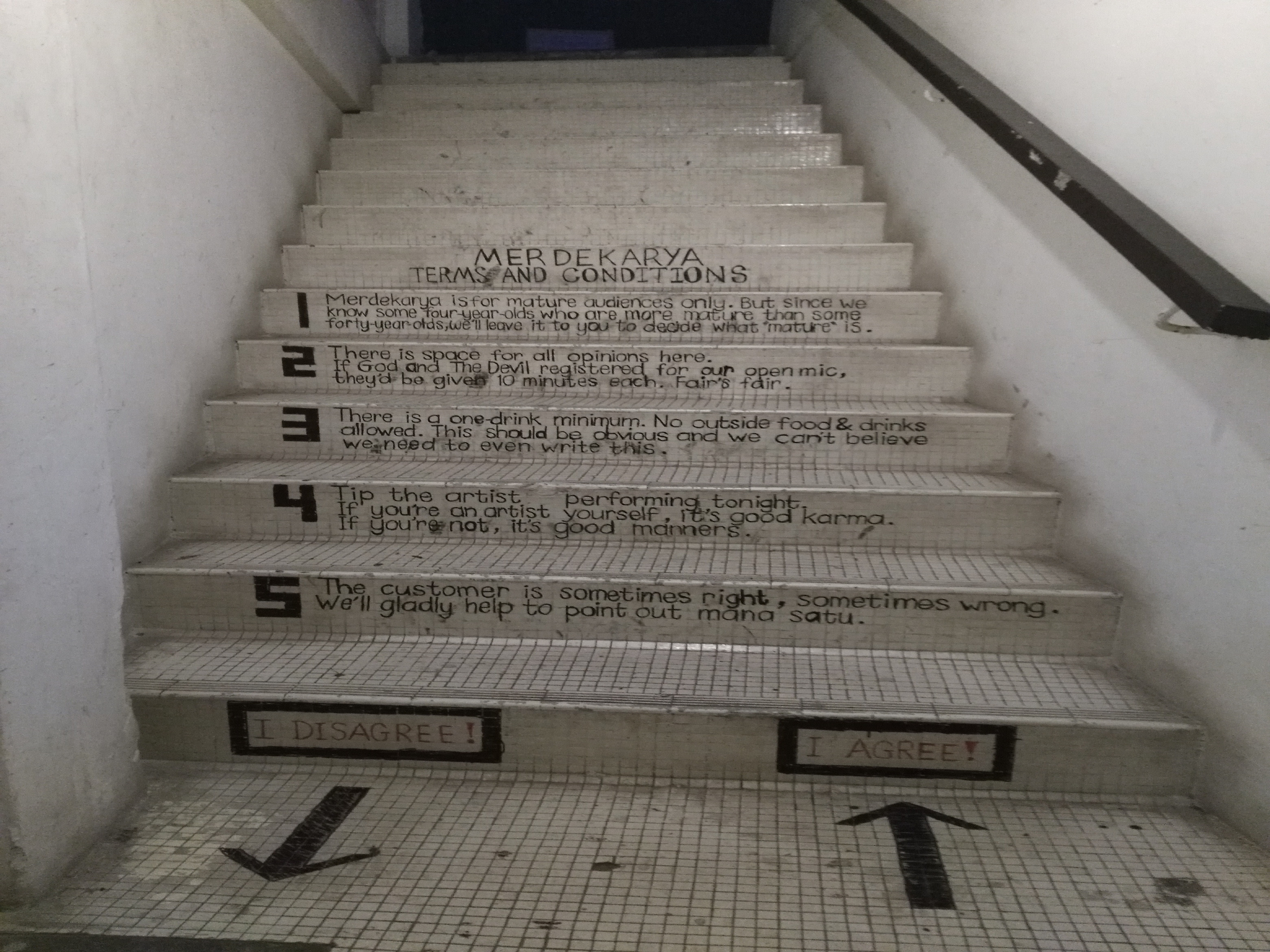

Holloween @ Merdekarya Featuring ROARM and “Panda Head Curry”

This week kicked off with me seeing Azmyl’s Yunor’s “joke band”, ROARM, at Merdekarya, a well-known bar/open-mic venue in Kuala Lumpur for the occasion of Halloween. On the Uber ride back to my AirBnb, I was reminded of the diversity of extremeties of activities and convictions that exists in Kuala Lumpur regarding arts production and consumption. On the one hand, I had just witnessed a band that sung music largely about animals, singing/screaming repeatedly to a cacophanous blend of schizophrenic guitars backed by an awkward shaker and ungodly backing vocals imitating the sounds of animals at completely random times throughout songs. Here’s a translation of one of the songs ROARM performed this night entitled “Aku Burung Gagak”:

I Am A Crow Bird (Hahaha):

I am a crow bird (X 12)

Hahahahaha hahahahaha

Look at me fly

I’m great, I can fly

Not like you all

I shit on your car

Because

I am a crow bird

To make matters more hysterical, this sort of performance was punctuated by the advertisement of a new drink being offered at the bar - an oversized “syringe” filled with lychee flavored liquor topped off with a lychee impaled onto the tip of the syringe - indeed the fallic symbol of all fallic symbols. Azmyl’s band was followed by an even more bewilderingly unique act, Panda Head Curry, which themed its entire performance on life on earth in the aftermath of a calamitous meteorite landing, which was faithfully re-enacted by the opening and closing of an umbrella that made it’s way thoughout the bar, on the heels of the main singer of the band who incessantly repeated, “What out, watch out for the meteorite” to the hysterical backing of retro-techno glory. Hear the entire album they performed live this night at this link. The funniest thing of all to me was that the Azmyl had to teach a course at Sunway University the next morning and the lead singer of Panda Head Curry had to go to work the next Tuesday morning to work on designing and building what my lesser mind registered as something having to do with particle physics.

In all things music that I’ve seriously engaged with from a young age, humor was virtually absent. Satire, absurdity, and silliness has squarely been outside of the realm of my musical horizons. Singing Bengali and Hindustani music, a very serious endeavor from early childhood, always entailed preservation of culture, the adoption of values and life lessons, exercises in creativity, meditation, etc. Similarly, the jazz and choral music that I embraced in college largely entailed the culture of academia, self-improvement, exposure to new musical traditions, competition, etc. Getting to see outrageous acts in Malaysia such as ROARM and Panda Head Curry and more subtle yet equally boisterous groups like Jono Terbakar and Jodhokemil back in Indonesia has been a real eye-opener. They’ve convinced me of humor’s entitlement to rhythm and melody and the need for all of us in the business of “creating art” to lighten up a bit from time to time.

Sheikh Aleey: The Power of Dhikr

I introduced Sheikh Aleey Abdul Qadir in last week’s post, which documented my travels to Madrasa Al Aliyah in Seremban, where he leads prayers and dhikr’s at. There, I witnessed live dhikr for the first time really. Conveniently, I discovered that Sheikh Aleey would be giving a talk entitled “The Power of Dhikr” at the newly built HAK Community Center in Kuala Lumpur this week. The talk was well-attended, and I came out of it with a handful of helpful concepts and practices. I’d like to describe just a bit about the first of these which is the difference between the constructive analysis of believers as compared with non-analytical believers and the deconstructive analysis of disbelievers as compared with non-analytical disbelievers. Sheikh Aleey holds that the most zealous believers are steadfast in their belief and vigorous in servicing God and humanity due to analyzing all aspects of life and what God has given us and coming up with rationale’s that point towards understanding God’s ways or God’s mysteries. On the flip side, the most disbelieving of disbelievers seek to analyze religious doctrine in order to invalidate religious fundamentals or premises. For instance, the deconstructively analyzing disbeliever may point to the fact that there isn’t necessarily observable evidence for the existence of God/gods (hence religion as a belief in God/gods or a belief system) and thus conclude that, for all intensive purposes, higher power and divinity is a figment of our imagination. A constructively analyzing disbeliever would recognize the view that God purposely leaves it up to us to believe in Him rather than to simply “know” that he exists as a result of being provided with concrete evidence of His existence (e.g. him simply revealing Himself in front of all of us). In a believer’s view, it’s God’s plan for humans to be tested on this Earth to choose to believe in Him and thereby choose good over bad and thereby seal one’s fate in heaven or hell. Thus, given that life is a test, God is not meant to simply physically reveal Himself to us as that would defeat the purpose of a test of people’s faith and unconditional servitude. Thus, constructive and deconstructive analysts have radically different responses to aspects of life and the nature of existence vis a vis divinity. The former rationalizes to validate and the other rationalizes to invalidate. Sheikh Aleey states that being a constructive analyzing believer is preferrable to being a “non-thinking” blindly following one, because the former generally feels more conviction in their belief.

Meena Loshini’s Kuchipudi Rangapravesam

I was naive to think that I would not learn something or gain some insight into my Watson project by attending the next event that I will describe. It happens that whatever I do on this travel fellowship, be it checking out a calligraphy exhibition or participating in a pie eating contest (okay maybe not so much the latter), always leads to additional insight regarding my Watson project. Thus, before checking out the Meena Loshini’s rangapravesam (similar to a Bharatnatym arangetram at the Temple of Fine Arts this past Saturday, I did not think that I’d be making an argument for the permissibility of performance arts production and consumption in Islam in a talk using this example the day after (more on this talk I gave below). I won’t get into the details as to what exactly kuchipudi is (I honestly don’t know much about it myself) or what an arangetram entails, let alon the history and mission of the Temple of Fine Arts. I presume that all of this can be Googled. Though the Hadith’s predilection to make blunt anti-music/musical instruments or anti-dance accusations seems to come out of nowhere, I and others I’ve discussed this issue with on my travels hold that the culture of music and dance in pre-Islamic Arabia has a lot to do with the negative statements that the Prophet Muhammad and his companions sometimes had to say towards music making and listening. This goes back to my previous post in which I wrote the following after reflecting on my interview with Mr. Ismail Ahmed, director of the center for culture at Universiti Sains Islam Malaysia (Univeristy of Islamic Sciences Malaysia).

Music making in pre-Islamic was often the domain of entertainer courtesans, both free women and slave women alike, who played instruments, sang, and danced in front of their largely males for their entertainment and pleasure. These women were also essentially bartenders for such nights out, pouring wine into the cups of their clients and/or slave masters throughout the night. These women would also provide sexual services to such men prostituting themselves for money or out of obligation. Surely, this was far from the the only musical culture available to average Arabs before, during, and after the Prophet Muhammad’s time. Music divorced from such debauchery surely existed as forms of story telling and entertainment among the common folk of Arabia. Nonetheless, the courtesan entertainment culture pre-Islamic Arabia cannot be neglected.

With this information in mind, it’s no wonder that the Prophet Muhammad and his companions had reservations for embracing music/dance and skepticism towards the lifestyles of musicians/dancers. Having finished watching Meena Loshini dance/act out a string of enactments of divine scenes/narratives to the accompaniment of a small musical ensemble during her two hour debut recital as per the tradition of kuchipudi pedagogy and culture, I couldn’t help but be slapped in the face by the drastic difference in the conception, status, and function of music/dancing of kuchipudi performance in Hindu culture as compared with the predominating “popular” music and music cultures of the day in sixth and seventh century society in Mecca. What would Islamic law have to say about music and dancing if the Quran were to have been revealed to a prophet from Southern India in the 7th century. In a culture in which impersonating deities through dance, drama, and song is regarded as a divine artform that must be mastered through years upon years of close study with a master/guru says a lot about what such a culture has to say about the conception, status, and function of dance, drama, and song. As opposed to a culture in which music and dance was commonly associated with slave women or prostitutes singing and dancing to their slave masters or clients as likely precursers to full-on sexual acitivity, the culture of kuchipudi pedagogy and performance regards vibration/movement/dance as sacrosanct. Vibration/movement/dance is the very conception of the universe, the method par excellence for worship, etc. A Hindu dancer in the 7th century let alone the 21st century is far, far away from a 7th century slave woman in a meccan harem. Of course, hypotheticals aren’t always allowed or considered very valid in discourse on Islamic law, but it seems to me that if the purpose of Quranic revelation was to guide humanity to worship God, do good, and avoid sin (i.e. love God), the issue of music and dancing for women in Islam may have been a non-issue if the Quran were to have been revealed to 7th century Tamilian society. Of course, the religious orthodox camp might argue that such hypotheticals are meaningless and severly misguided, because God simply does what He wills, and if he wills for singing and dancing especially to be regarded as a sin, it does not make a difference if a native population does not consider it to be a sin, in which case, it makes that much more sense for God to have revealed the Quran to a people who were engaging with music and dance in a way that God would eventually reveal to them to be heinous acts. Even more, some religious Muslims might argue that the Quran and Hadith might have had even more vitriolic material to shed about music, dance, and drama had the Quran been revealed to a prophet in Hindu Southern India, in which the arts were intimately tied with polytheistic worship - perhaps the most major of major no-no’s in Islam.

Sharing Session @ Duo Treno Cafe

So this was the kind of philosophizing that I dug myself into while engaging in a sharing session this past Sunday at the Duo Treno Cafe in Kuala Lumpur. The session/discussion was recorded and produced by UmranTV, a volunteer group that produces talks and discussions related to Islam and makes it a point for much of their content to be in English for broadcasting on YouTube. I showed up to the event, having not slept in a couple of days, with fifty pages of single spaced writing, foolishly thinking that I could get away with reading through a wad of presentation notes verbatim. Upon arriving to the venue, I was told that I would instead be having a casual, filmed discussion with Ms. Elfa, the host for the afternoon. Therefore, I resolved to elaborate on key snippets from my notes, allowing for back and forth between myself and Ms. Elfa. Going into our discussion, I had been operating under the assumption that musicking is permissible as long as it does not lead to or is associated with more clearly sinful acts, largely informed by conversations with imaams and scholars I’d had prior to this presentation. Ms. Elfa, along with a number of Muslims in especially more conservative states, raise the concern that many Muslims fear listening to or making music due to metaphysical properties or effects of musicking which may have a subconscious effect on the human soul or character. Such individuals fear, and I use the word fear quite literally, that by listening to or playing music, they open themselves up to the opportunity for Satan to “whisper” to them, i.e. influence them negatively. This claim, a metaphysical one, cannot be put to the test in a science lab. The only way to address this concern is to engage in Quranic interpretation, exegesis, etc. to disprove the notion that Satan has a hold on all musicking activities. Referring to the source texts of the religion is the only way to combat such opinions. On the less metaphysical end of things, Elfa was also concerned about scientific studies which point to detrimental effects that music listening has on the mind and body as opposed to character or the soul. Understandably, she was not able to cite the methodology or results of these studies on the spot, but I hear that they do exist. (I’ll treat the issue of the aims and methodologies of such studies in a post to come). Other Muslims yet may fear music making or listening because of specific hadith which they interpret literally, without caring to put things into context (e.g. denunciations of flute playing or stringed-instruments). Some people are completely fine accepting the notion that music is haram simply because God commands/wills it be so.

Swordfish + Concubine @ KLPAC

I topped off my week by attending a musical/drama highly worth remembering entitled “Swordfish + Concubine”, by Kee Thuan Chye. Similar to the diversity of extremeties that exist in the actions and thoughts of Malaysian citizens vis a vis issues in religion, attending this event opened my eyes to the diversity of politial convictions in Malaysia. In light of constantly hearing about the dangers of being charged with defamation and treason in Malaysia from my Uber drivers, it was difficult for me to believe my eyes and ears at especially blasphemous points during the “Swordfish + Concubine” showing I witnessed. Such points included impalement through the anus and out the mouth actually being acted out on stage as opposed to being left to the human imagination. Numerous sexual references and explicit conversations about sex made its way into the comical and dramatic mix. Most poignantly, the script included obvious enough references to bad governmental policies and corruption for even an ignorant American like myself to grasp the highly cynical stance being championed. Criticisms, seemingly of the Malaysian government, included the incompetency and idiocy of people in power, nepotism, a lack of checks and balances, and corrupt government schemes such as the “people’s wealth fund” which is an obvious front that allows one of the government’s minister’s and his sneaky cohort of lesser officials to siphon off money away from the government into their greasy pockets. All of this would be unthinkable to freely take place in the auspices of religious conservatives and government officials. This showing of “Swordfish + Concubine” took place at the Kuala Lumpur Performing Arts Center (KLPAC), a private owned and run performing arts space. It goes without saying that government officials would not allow such a staging to occur in one of their own administered event spaces or officially recognized or sponsored occasions. The fact that the play was staged in English at the KLPAC further decreases access for the average conservative Muslim to criticize. Private institutions and the English language thus serve as buffers or buttresses against persecution or censorship on religious or political grounds.

As a musician, one of the coolest parts of the show was the musical accompaniment provided by “Rhythm in Bronze”. As opposed to appropriating the totality of the concept of a musical in the West to the Malaysian context, it seems to me that creatives in post-colonial nations are becoming more selective in their borrowing decisions from Western cultural or artistic models. Rather than going with the default instrumentation for musicals (i.e. pop/rock band instruments perhaps with some Western European orchestral elements) Rhythm in Bronze only features karawitan instruments from Nutansara, i.e. the Malay Archipelago including modern-day Brunei, Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore, the Philippines, and East Timor. Interestingly enough, it seemed to me that the tuning of such instruments was still in line with 12-tone equal temperament, unmistakably a musical innovation of Western/Central Europe. This is does not discredit my argument, but rather bolsters it. It demonstrates the exent to which musical ensembles in post-colonial states are selective in their appropriating elements of Europen or American musical traditions.

Tasty Treats in Kuala Lumpur: Pt. 2

Lucky for you, I did not do any formal interviewing this week, meaning this post was significantly shorter than others that I’ve done. Unfortunately, I won’t be sparing you next week. For now though, bon apetit.