The Last Stan

04 Feb 2018

Reading time ~21 minutes

This week, in addition to doing the usual full-length interviews that I do with people, I tried doing a number of rapid-fire interviews with mosquegoers and random people on the streets. I’d say that about 1 in 3 strangers that my interpreter and I approached were receptive to recording their thoughts on camera. A pretty decent ratio, if I may say so myself. Anyhow, this post is entitled the “The Last Stan”, because I finally made my way by shared taxi to my final destination in Central Asia ending in the suffix, you guessed it, ““-stan”: Uzbekistan. More on that later. For now, here’s some interview goodness from my last days in Osh, Kyrgyzstan.

Interviews

Asilbek Abduganiev

Asilbek Abduganiev is a master’s degree student at Osh State University, Faculty of Arts. While working towards his degree, he’s produced two albums of Islamic music, a kid’s album and one for general consumption. He began making music at a young age, a long time fan of the likes of Sami Yusuf and Maher Zain. Much of his output is translations of songs by such giants of the nasheed music industry. Asilbek’s family has been highly shariah-cognizant since his childhood, though his family’s Islamic sensibilities were never a hindrance to his love for music though. It was only after associating with the Tablighi Jamat in Osh that he was first exposed to hadith or quran inspired artsphobic noises. Asilbek reported that the majority of Tablighis in his experience were firmly against music, dance, and figurative painting. Rather than simply giving into their conclusions on the issues, he took it into his own hands to look into the matter in some more depth. Over the years, he’s found more and more evidence of Islamic scholars in history who deemed music to be either entirely or mostly permissible.

In particular, Asilbek mentioned that Imam Ghazali held that Islam prohibits things which are unnatural and permits things which are natural. Given that most all babies take delight in and start immediately dancing to the sound of music, it follows that our predispositions for music and dance must be hardwired into the human genome, so to speak. Asilbek likened this predisposition to a baby’s reflex to cry when hungry. Other scholars like Imam Shafi and Imam Hanbali were perhaps a bit more careful to spell out that music can be harmful if not properly contained and moderated. From time to time, Asilbek is approached by people, at mosques, concerts, etc., who insist that music is haram. Just as he did with me in the course of our interview, he tries his best to explain to such people that music must be conditionally permissible as various Islamic scholars have mentioned throughout history and as there exist several hadith that confirm the existence of “music” making and listening in the Prophet Muhammad’s company which he did not object to. Others Asilbek has spoken to on this matter insist that singing (especially for men) might be okay, but musical instruments are most definitely haram. To this particular point, Asilbek retorts that there is only mention of a few instruments being problematic in several hadith reports of varying levels of authenticity or reliability. The vast majority of instruments that he employs or wishes to employ in future productions including synthesizers and traditional Kyrgyz instruments have no mention in the Quran or Hadith, a highly literalist though valid perspective to take.

Lastly, Asilbek maintains that he only sings songs for the sake of Allah, the Prophet Muhammad, and Islam. Most of his songs are intended to inspire people to abide by shariah. He believes that one of the central points of Islam is to encourage moderation - neither spending one’s life entirely at the keyboard nor refusing to listen to any music at all. Ideal Islam in his opinion is a moderate one compatible with native traditions. The average Muslim in Osh, for instance, need not constantly think of God and ought not always dress like Bedouins especially since the climate in Kyrgyzstan is drastically different than that of the Arabian Peninsula. Asilbek articulated that Muslims who place the culture and social milieu of the early Muslims on a golden pedestal are misguided, as they value external attributes at the expense of internal ones. He likes to remind people that Islam is very broad - prescribing not just orthopraxy and orthodoxy but also less tangible aspects of the human experience.

Abdulmanaf Sadikov

Abdulmanaf Sadikov is currently working towards a Bachelor’s Degree in theology from Osh State University, Faculty of Theology, the same faculty that Asilbek is currently studying at. I had the good fortune of meeting both Abdulmanaf and Asilbek through Ferhat Gokce from last week’s post. As with Asilbek, both religion and the arts have factored into Abdulmanaf’s life since early childhood. Growing up, many of his maternal relatives were either artists or into the arts, though art has mostly been one of his hobbies. Unlike other practicing Muslim artists I’ve interviewed who produce “Islamic art”, Abdulmanaf does not only produce “Islamic art”. In addition to doing calligraphy and abstract art, mainstays of “Islamic” visual art, he also enjoys drawing potraits of and photographing people. Given just how unique he is in this regard, I had to ask Abdulmanaf exactly how he gets away with doing both “Islamic” and “secular” art. Firstly, Abdulmanaf raised the oft-repeated point made by Muslim visual artists that figurative depictions are halal in so far as one does not intend to or actually worship such depictions, as the pre-Islamic Arabs did with their various idols of gods. That being said, Abdulmanaf did mention that he avoids drawing animals, which did not exactly register with me given that he routinely does human portraits. Even more challenging were a series of his calligraphic works in the shapes of various animals. One such work spells out Surah Al-Fil literally in the shape of an elephant, as the surah relates the story of an army of elephants led by an agressor attempting to sack Mecca before the advent of Islam which was brutally destroyed by Allah. In such cases, it’s difficult to say whether illustrations are simply texts or figurative depiction. In this way, such illustrations are perhaps loopholes of sorts for Muslim artists to get away with figurative depictions through their extraordinary powers of imagination.

Abdulmanaf is certainly not a proponent of all Muslims engaging in less typically shariah-compliant forms of art willy nilly though. He made clear to me that he only feels certain of what he does after having done his homework on the matter at hand. Now that he’s both informally and formally studied religion, he feels fairly confident about making independent decisions on what is okay and not okay for him to draw. He trusts that he will not cross religious boundaries given the level of knowledge and experience that he currently possesses. Nonetheless, he does worry for people who lack in religious knowledge who engage with the arts, be it art producers or consumers. Such people may not have the discretion to choose right over wrong or to interpret something one way over another. For instance, Abdulmanaf’s reasoning for and intention behind drawing a portrait of a young woman may be completely different from those of someone not as religious and well-intentioned as he is. He fears that in the face of art that depicts taboo or haram subjects in films or pictures, for instance, 50% of Muslims may be enlightened enough to take such depictions as sources of information and reminders to avoid that which is evil or inappropriate in life. The other half of the Muslim umma today with less discretion, as Abdulmanaf sees it, may take such depictions to be models of things which ought to be emulated in society. Abdulmanaf finds himself having to justify his own position on figurative depictions in Islam especially during his art exhibitions. Event attendees and others have insisted to him that much of his artwork is haram. Nevertheless, he tries his best to firmly hold his ground as he did during our interview and kindly suggest to such people that they ought to look into the matter more deeply before being so sure of their own opinions.

Elmira Ismanova

When I learned about the opportunity to interview Elmira Ismanova (Instagram: @ismanova_fashion), modest clothing line designer, I was not entirely sure what to expect. A part of me felt that an interview with Elmira could end up being not so relevant to my Watson project. Shortly into our interview at a cafe in Osh, I realized just how wrong I was. As it transpired, our interview hit the mark as it’s turned me onto broadening the scope of my project even more from Islam and arts to Islam and culture (originally, I was only thinking about Islam and music). As of now, I realize that my Watson project has bearing on not just music or arts, but rather culture more generally. In my experience, Muslim artists are similar in that they foremost intend for the “Islamic” forms of music, dance, theater, film, paintings, sculpture, and/or clothing they produce to be viable alternatives to their mainstream, secular counterparts in Muslim majority and non-Muslim majority countries today. This point is key as it explains why modest clothing line pioneers such Elmira take it upon themselves for their clothing to be so stylish or fashionable. Upon first inspection, one may find it hypocritical or ironic that someone purporting to make or wear “modest clothing” would take it upon themselves to be so fashionable, what with heavy makeup, flashy jewerly, and eye-catching clothing. Similarly, one is initially perplexed at the existence of Islamic music in the form of death metal or punk rock until one realizes that such forms of music actually provide average Muslims with the opportunity to choose to listen to a band like Al Farabi Band as opposed to their not so shariah-compliant counterparts which they may already adore such as Metallica or Slipknot. Thus, even though clothing from Elmira’s fashion line may not be so modest in that they may be just as stunning or eye-catching as that of more mainstream brands, at least such clothing covers up the “intimate” parts of a woman’s body (awrah) as detailed in the Quran.

Elmira did not grow up in a particularly religious household. Though her father was capable at quranic recitation and leading prayer, her mother was from a relatively secular, middle-class background. She did not start actively learning about and practicing Islam until she and her sisters started wearing the hijab. Her commitment to Islam intensified as a student of law in Russia, where discourse on and media coverage of Islamophobia were becoming more prevalent. Rather than feeling turned off to Islam though, she felt the need to defend and more actively represent the religion she’d inherited. Her beliefs and actions in the face of such adversity resonates with the following saying she shared with me, which is apparently commonly known among Muslims in her experience, and I paraphrase: “When people do bad things to Muslims, they become more Islamized.”

Reading up on Islam led Elmira to reassess much of her pre-Islamic lifestyle and pursuits. Foremost, she came to believe that law was not a fitting profession for Muslim women In her opinion, the woman in Islamic history whom ought to be emulated most was the Prophet Muhammad’s first wife, Khadija, a very successful business woman in her day. Addtiionally, design was particularly appealing to Elmira because her mother and one of her primary school teachers among others had always encouraged her to pursue a career in the field. Even more, she felt that designing and making clothing were particularly fitting engagements for Muslim women as it requires one to work with one’s hands. In addition to rethinking her career path, Elmira also gave up her ambitions in music and acting. Her choice to cover up came as a shocker to her mother who had long expected that she would become a musician or actress at some point in her life. After graduating from five years of guitar studies at a music school in Kyrgyzstan, she put a hard stop to music making. Elmira recounted to me the exact moment when she knew for certain that she would no longer make music for good. One day, in the mixed company of male and female friends, she remembers tuning her guitar to play a few songs when suddenly one of her guitar strings snapped. She felt especially sure that Allah was signalling her to stop making music for good when another one of her guitar strings promptly broke when attempting to tune her guitar again. Regarding Islam and arts, Elmira believes that figurative depictions are haram as evidence in the well-known hadith stating that people who create figurative depictions will be asked by Allah to give life to their creations on judgement day, the implication of such a statement being that such people will miserably fail at doing so and consequently be punished for their attempts at “creating life”. This explains the lack of human faces and/or animals in Elmira’s designs or that of most if not all other Islamic clothing lines. I didn’t get a chance to ask Elmira exactly why she thinks that Muslim women ideally should not be lawyers or take up other similarly demanding professions for that matter. I’d come across a number viewpoints regarding what women should and should not do both in person and on the internet, so Elmira’s thoughts on this matter did not come to me as something completely unexpected. She told me that she’s happy to have come to each of these decisions sooner than later, because of the notion that, in Islam, unconsiously sinning accounts for a single sin while consciously sinning causes double sin. This perhaps explains why the acquisition of knowledge particularly with regards to matters of shariah is enjoined upon all Muslims in the Quran. That is, one is not exonerated from sin just because one was not aware that one was sinning. Elmira realizes that hidayah (guidance) comes to all people whenever Allah wills, so she is not upset at the fact that she spent so much of her time, energy, and money towards her legal and musical studies.

Elmira’s primary motivation for providing people with shariah-compliant forms of fashion is neither to make money nor win recognition. Rather, she mentioned that she is mainly driven to design clothing for the sake of dawat/dakwah. She admits that she’s not qualified to preach at people about Islam. However her God-given talent for design makes her an excellent candidate to turn people on to Islam. When people see her on the street or at events, they often ask her about her clothing. From there she is usually able to tell them something about Islam. One would imagine that such people would then take it upon themselves to look into the religion some more. For some, modest fashion may be a catalyst for people to embrace Islam just as Islamic music and even the sound of the adhan or quranic recitation can be a strong draw for new entrants to Islam. Elmira told me that she doesn’t want to be just another “covered girl” in society. She refers to the fact that the Prophet Muhammad encouraged Muslims to adopt the culture and customs of non-Muslims in order to attract more people to Islam. Thus, she gains inspiration from all kinds of fashion to come up with designs for her clothing line.

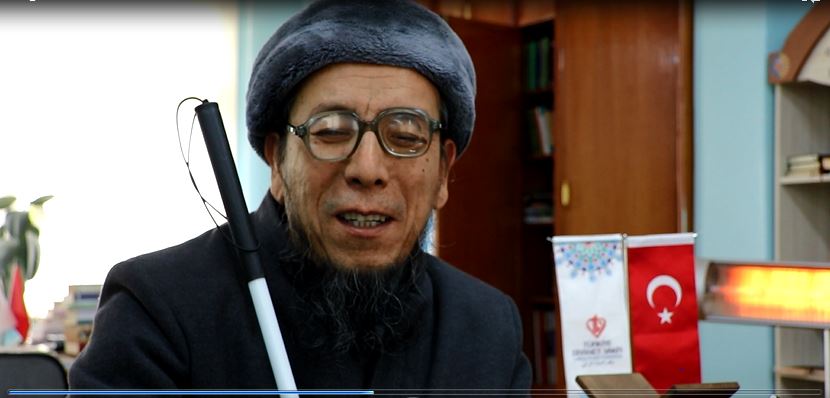

Ustad Umar

After failing to get imams at various mosques in Central Asia to agree to do a filmed interview for my project, I finally managed track down one religious teacher willing to grant me the favor. Umarjan Imamberdiev (aka. Ustad Umar) provides Islamic instruction to visually impaired students. He told me that he was born into a family of moderate Muslims, most of whom possessed limited understanding and exposure to Islam. Nonetheless, he was especially attracted to the religion from a young age, finishing the Quran of his own accord at age 15. Being unsatisfied with translations of the the Quran into Cyrillic braille, he took it upon himself to learn Arabic braille to read the Quran in its original language. He attributes this achievement to none other than Allah, whom he thanks for having blessed him with a strong disposition towards Islam.

Though Ustad Umar did not speak for very long on the topic of arts permissibility in Islam during our interview, I felt that his few words on the matter were poignant. From time to time, he’s encountered opinions on whether or not music is haram or halal. For the most part, however, he told me that he does not interact with very many people and the topic of arts permissibility has come up less often in such interactions than other subjects having to do with Islam. From whatever he has encountered on the issue, however, he feels that it’s probably best that people do not partake in an too much music making. He related the story of how a sahaba (companion of the Prophet) named Abdullah Ibn Masood (RA) once suggested, while passing by him singing for a party of listeners, that a singer/musician named Zazan ought to recite the Quran rather entertain guests with secular music. He also mentioned that musical instruments are exhausting to his ears, a point that intitially struck me as odd but later appeared to me to be a perfectly plausible phenomenon. Ustad Umar vastly prefers the sounds of nature including waterfalls and birds as opposed to man-made musical instruments. What “music” he does listen to is mostly in the form of a capella nasheed. Ustad Umar said that it’s probably okay for people to make and listen to music even with instruments as long as one does not transgress in the process of music making and listening. Although he did not explicitly mention that humans should not exercise their creativities towards arts production and consumption, several of his comments suggested this. By mentioning that Allah is the original and unparalleled creator of the universe, Ustad Umar implied that not a single man-made creation comes close to the glory of His creation and that He is the one who has endowed all humans with whatever limited creative abilities we claim to be our own. Ustad Umar emphasized that we often take God’s creations for granted - rivers, oceans, flowers, the sky, etc. I got the sense that he believes that human beings need not “waste their time” with creating music, paintings, sculptures, etc. when they could easily behold Allah’s bounty.

Idris Aitbaev

I first heard of Idris Aitbaev from a Kyrgyzstani citizen I randomly met with back in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. She mentioned to me that I needed to meet with him due to his superb abilities as an akyn (improviser for voice & komuz) in over five languages including English (fast forward to 4:47). Rougly five months later, there I was in Mr. Aitbaev’s office at the Babur Theater in Osh, interviewing him about his thoughts on arts permissibility in Islam. The first thing that Mr. Aitbaev told me during our meeting was that he woke up every morning to the sound of his father reciting the Quran, his favorite sound growing up. Though he was provided with religious knowledge from his father, none of Mr. Aitbaev’s family members are into the arts. Nonetheless, he started writing poetry about things he cared about including religion as a university student. From the onset of our meeting, it was clear to me that Mr. Aitbaev is fundamentally concerned with one thing in life - getting himself and as many other people as possible to live life as ordained by Allah in order to reach paradise. It just so happens that he is extremely talented at languages and music, allowing him to introduce people to Islamic values and criticize societal problems in highly creative ways. Mr. Aitbaev was impressively clear-cut regarding his position on the permissibilities of music and dance in Islam: music is haram if it leads you to stop obeying Allah’s mandates. He likened music to water in the sense that music can enter into and meddle with one’s heart just as water can cause damage by seep into the smallest of openings. Even the tiniest amount of music can thus ruin one’s iman (belief in Allah), given unfavorable conditions. I imagine that if someone had made this statement in my presence before the start of my fellowship, I’m afraid that I might have simply disregarded it from a place of heavy skepticism. Having reflected on the issues at hand for the past six months of travelling, however, I feel that I am realizing more and more just how powerful music and dance are and beginning to grasp the saying “with great power comes great responsibility” in a new light. From what I could gather from Mr. Aitbaev’s words, music ought not be so attractive that it lingers in one’s hearts more so than the sounds and meaning of quranic recitation. In general, Mr. Aitbaev advises people not to listen to too much music, especially not the likes of rap, rock, or hip-hop music. That being said, he emphasized that if a song or piece of music brings one closer to divinity, then one should have no reservations about engaging with such music. He mentioned that some kinds of music trigger people to immediately think about Allah or the Prophet, while other kinds of music immediately drag people down into satanic depths. He posits that this explains why Islamic scholars throughout history have had reservations towards approving of music in its entirety. He believes that various aspects of the arts eventually became haram over the years because human beings took things to the extreme. Instead of thinking about their religious obligations and perparing for the afterlife, too many artists in Mr. Aitbaev’s opinion mechanistically devote themselves to their crafts. Too many painters paint all day and night and too many musicians make compose at the piano or computer without taking breaks for prayer. Mr. Aitbaev maintains that such artists cannot possibly be invested in thinking about their love for God or their sins if they are so addicted to their crafts.

Hello Tashkent, Uzbekistan

I have to say that I will be missing Kyrgyzstan pretty hard. Even though all my time in the mountainous country was spent in the snowy and chilly days of winter, the country and its people has left a nostalgic mark on me. Having arrived in Tashkent at the tail end of this past week, I have not been able to get much done in the way of project stuff. For the most part, I’ve simply been getting a feel for the city which happens to be the largest in Central Asia. One of the bigger differences that I’ve detected between here and where I spent most of my time back in Kyrgyzstan in Bishkek is the size and quality of the roads here in Tashkent. Everything seems to be twice as far as they really are out here as the roads are impressively wide and well-maintained. Admittedly, sometimes things can feel a bit lonely, unlike back in Bishkek where there are generally people walking about most everywhere in town. The number of police on the streets is not very different between the two “-stans”, though the police here seem to do a bit more work than those in Bishkek. Everytime you enter the underground (oh yeah, that’s a pretty big difference too - there’s a really nice subway system here in Tashkent) police guards check your bags at multiple points during your journey. I hear that filming in the underground was strictly prohibited until just recently. Anyhow, I am a bit perplexed as to how the government here can fund so many people constantly on patrol in the city. A couple of natives I’ve spoken to here mention that it makes things safer for everyone, which I can understand.

Tasty Treats in Osh and Tashkent

I’m gonna butter your bread…